Published 04/10/2015

Commissioned in 1932 by William Valentiner, the Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Detroit Industry fresco cycle was considered by Rivera to be his finest work. Completed in an astounding eight months, the commission only had one original rule: it must relate to the development of industry in the history of its patron city.

| Diego Rivera conceived his fresco cycle as a tribute to Detroit's manufacturing base and workforce. The project was financed by Henry Ford's son, Edsel B. Ford, who was then president of the Ford Motor Company. Encompassing all four walls of the Garden Court in the museum, the murals (27 in all) are rife with Christian themes and utopian symbolism. In order to research the automobile industry, Rivera and Frida Kahlo toured the Ford River Rouge plant in Dearborn, Michigan. In its pinnacle in the 1930s, the factory employed 100,000 workers and used over 120 miles of conveyor belts in a sprawling mile-and-a-half wide, mile-long facility. Kahlo and Rivera took hours of footage, and hundreds of photographs in their research. Bridgeman recently uploaded several presentation drawings and charcoals from Rivera's preparatory stage along with photos of Rivera at work. |

|

Nature & Man in Harmony

The east wall is the beginning of the fresco cycle. The baby in the bulb motif (above) is flanked by two fertility figures and fruits and vegetables indigenous to Michigan. Rivera means to connect everything humankind does is ultimately connected to the earth and nature. It is said that originally the design was supposed to be a beet bulb, but that Frida had recently had a miscarriage and Rivera changed the graphic to a baby. Every icon in the fresco cycle is meant to play off of another part of the room. In this case, the east wall's agricultural symbols play off the west wall's technology and air motif. The west wall is also a statement on good industry vs. bad industry, with the juxtaposition of an airplane against a warplane, and a dove against a hawk.

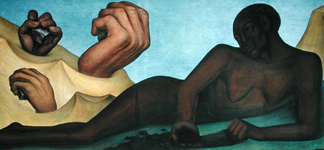

The Four Races & Four Elements

On the north and south walls sit four female sentries, each an archetype of one of the four races: European, Asian, African and Native American (see images below). Each woman holds an essential element of the earth in her hand: iron,coal, limestone and sand (all four of these elements go into the making of steel). Each element and race, although different, are presented equally. Interestingly, Rivera based the European face on one of his assistants, Lucienne Bloch, while the African face was based on the housekeeper of the hotel Rivera lived in during the project.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Factory Lives and Breathes

|

Rivera makes the factory look full of life, with his depiction of the production line on the north wall. The scene is huge, at 75 feet long by 17 feet high, and the sense of movement guides the viewer through the scene as if they are on a conveyor belt. The line of workers (detail above) gives a sense of rythmic movement, back and forth. It also conveys the comraderie of the workers and a palpable harmony between worker and machine. In the visual center of the panel (Rivera is said to have used the Golden Mean - an ideal ratio of thirds), sits the furnace. This is the hub of the factory, the heart of the beast. Rivera designed the furnace in this specific location on the wall because he wanted it to glow when afternoon sunlight hits that exact spot. Guiding the eye to the furnace are two rows of spindles which purposefully appear as ancient Toltec guardian figures. Through this visual, Rivera wanted to connect the pre-industrial age with the modern era of science. View more details from the north wall factory panel. |

|

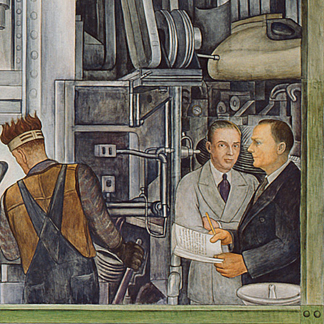

Harking back to the Renaissance period, Rivera painted his patrons into the cycle. In the bottom right corner the south wall, Edsel Ford and William Valentiner oversee the final stage of the automobile manufacturing process, the car's exterior. In another reference to ancient civilizations, a huge stamping press appears as a modern Aztec goddess of creation, Coatlicue. When the murals were unveiled in 1933, they were met with controversy. Many objected to Rivera's depiction of different races, some people called them blasphemous, while still others labeled the nudes pornographic. The project was contentious from the outset as the hiring of a Mexican artist in a time of high unemployment seemed, to many, un-American. And last, but certainly not least, Rivera's Communist political leanings were highly suspect to many. In the end, both Edsel Ford and the museum stood behind Rivera and his masterpiece and it has become Detroit's most celebrated icon. View all images of the Detroit Industry cycle available online. If you don't find the detail you are looking for, email newyork@bridgemanart.com, and we'll source the image for you. |

|

We've only scratched the surface of the rich meaning and detail in Rivera's frescoes. The Detroit Institute of Arts website has an incredible online tour, which we recommend to all who want more information.

All images are from the Detroit Institute of Arts, USA / Gift of Edsel B. Ford. Copyright clearance for Detroit Industry handled by Bridgeman Art Library on behalf of the Detroit Institute of Arts.