Published 06/04/2011

In addition to the keyword links in the following article, the following collections have particularly rich selections of Civil War material including: photographs, ephemera, paintings, maps, portraits, objects and drawings.

- The Civil War Archive

- The Stapleton Collection

- Virginia Historical Society

- Peter Newark Pictures

- American Antiquarian Society

- Atwater Kent Museum

- Chicago History Museum

If you have an upcoming project focused on the Civil War era and need research assistance, drop us a line, tell us what you are looking for and we'll do the hard part.

| 19th Century "Don't ask, don't tell" Both the Union and the Confederate armies forbade women to enlist. However, many women did fight by disguising themselves and enlisting as men. Due to their necessary secrecy it is impossible to know how many women fought during the Civil War, but evidence has been found that confirms the existence of over 240 women who impersonated men and fought for the Union and Confederate Armies. Mary Edwards Walker, a doctor, (left) went to Washington and tried to join the Union Army, but was denied a commission as a medical officer. So she volunteered anyway, and was the first - although unofficial - female surgeon in the US Army. President Johnson signed a bill in 1865 to award her with the Congressional Medal of Honor for Meritorious Service, but the honor was revoked in 1917 when the standards were changed to only include combatants. She refused to give the medal back, wearing it every day until her death two years later. |

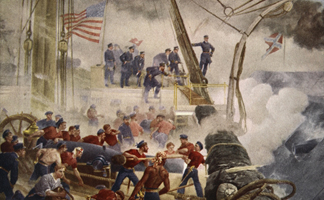

An American Battle, in France? The Battle of Cherbourg took place off the coast of Cherbourg, France between the USS Kearsage and the CSS Alabama. After a few successful commercial raiding missions in the Atlantic Ocean the CSS Alabama intended to get a few repairs done in France however, the USS Kearsage had been following the ship. As the CSS Alabama neared the port the rival ship was spotted, forcing the ship to turn around and fight in French waters. The CSS Alabama sunk after just over an hour of fighting. Painted twice by the French artist Edouard Manet (right), it is rumored that he witnessed the battle from the shore. |

|

| Spies in the Skies The Union and the Confederate armies both used hot air balloons during the Civil War. This was the first large-scale use of balloons in the military. The Union Army Balloon Corps was established and organized by a civilian, Prof. Thaddeus S. C. Lowe in 1861. Balloons were initially used for aerial map-making until General Irvin McDowell realized while surveying the battlefield at Bull Run in Lowe's balloon that they could be effective for reconnaissance. The information from these spy balloon would help gunners on the ground fire accurately at targets they could not see, a military first. The general attitude toward the use of balloons deteriorated after Lowe's resignation, and by August 1863 the Balloon Corps was disbanded. In the 19th century, the Corps were seen as a civilian group and none of the men received commissions for their service during the war. |

Farragut's Rallying Cry “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.” is attributed Admiral David Glasgow Farragut during the Battle of Mobile Bay. On August 5, 1864 Farragut was commanding the USS Hartford during the Battle of Mobile Bay when he shouted to the USS Brooklyn what their trouble was. They replied that there were torpedoes (a term used then for tethered naval mines). Farragut replied "Damn the torpedoes! Four bells. Captain Drayton, go ahead! Jouett, full speed!" The bulk of the fleet succeeded in entering the bay and Farragut won the battle. |

|

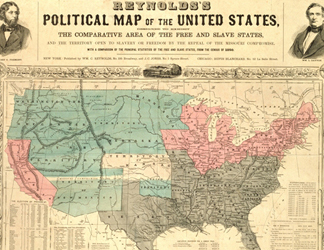

| "You say Manassas, I say Bull Run...." Both the Union and the Confederacy created their own names for each battle, usually resulting in each battle having two names. The Union often named battles for surrounding natural features that were prominent on or near the battlefield while the Confederates usually used the name of the nearest man-made landmark. For example, the North named the battle that occurred on July 21, 1861 Bull Run (a local river) while the South named it Manassas (the local town). Many modern accounts of Civil War battles use the names established by the North however, for some battles the Southern name has become the standard. In general, naming conventions were determined by the victor of the battle. |

The Horrors of War For All to See The American Civil War was the fourth war to be caught on camera, after the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), the Crimean War (1854–1856), and the Indian Rebellion of 1857. However, the work of photographs such as Mathew Brady and his employees are seen as the beginning of photojournalism. Due to the photographers slow process many admitted to staging scenes for their photographs as well as adding bodies and cannon balls to the image in order to show what they believed to be the nature of war. |

|

| A Presidential Union Army:

|

Fighting for the Cause When news of the fighting at Fort Sumter was heard, many free black men rushed to enlist in U.S. military units, however they were turned away because a Federal law dating from 1792 barred them from bearing arms for the U.S. army (even though black soldiers had served in the American Revolution and in the War of 1812). The Lincoln administration wrestled with the idea of authorizing the recruitment of black troops, concerned that such a move could prompt the border states to secede. By mid-1862 however, due to the escalating number of former slaves, the declining number of white volunteers, and the increasingly urgent personnel needs of the Union Army convinced President Lincoln to allow black soldiers to serve. After the Emancipation Proclamation was announced in January 1863, black recruitment was pursued in earnest. By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union forces) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. |

|

| Secession & Back Again Virginia voted to secede from the United States on April 17, 1861, after the Battle of Fort Sumter and Abraham Lincoln's call for volunteers. On April 24, Virginia joined the Confederate States of America, which chose Richmond as its capital. Delegates from the western areas of Virginia met at the Wheeling Convention, lasting from November 26, 1861 to February 18, 1862, and the Ordinance of Secession from Virginia was ratified on April 11, 1862. President Lincoln admitted West Virginia on the condition that a provision for the gradual abolition of slavery be inserted in its constitution. After the 1863 Wheeling Convention, 48 counties agreed to the terms and became West Virginia. West Virginia was the only state in the Union to secede from a Confederate state during the American Civil War. |